Hi friends,

This newsletter was supposed to be sent out in Feb. I had all the content ready except for this beginning bit, where I was supposed to share a little note to you. And this bit felt overwhelming and so I avoided it. Honestly, the return to so called normal life has been a whirlwind.

After 2 years, I travelled back to Uganda (where I work) in Feb and am here for three months. I met my colleagues and am working in-person from an office with more than thirty other people, after a very long time of working from an isolated corner of my room. I was so busy adapting to WFH life in 2020-21, that I didn’t even realize just how MUCH I missed being in office. The dressing up and packing your work bag, the big smiley morning greetings, the little counter to make yourself a cup of tea or coffee, asking how people were and if they had a good weekend, the colleagues who get you fruits from their gardens, the giving each other knowing looks when taking a zoom call together. The list goes on.

Coming back to office feels like an overwhelming hug which momentarily took away my ability to communicate as I was processing it all. Of course, almost two months in, I am also feeling a sense of fatigue from this new routine which my body is not used to anymore. But most of all, I am grateful that life finally seems to be moving on a bit and I have better ways to start my mornings than hopelessly refreshing Covid-19 stats webpages.

Sending love from Uganda,

Tvisha

About the book [Wiki]:

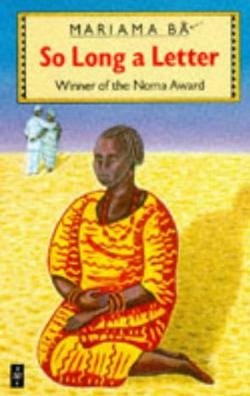

So Long a Letter (French: Une si longue lettre) is a semi-autobiographical epistolary novel originally written in French by the Senegalese writer Mariama Bâ. It was her first novel. Its theme is the condition of women in Western African society. The novel is often used in literature classes focusing on women's roles in post-colonial Africa. It won the first Noma Award for Publishing in Africa in 1980.

So Long a Letter is written as a series of entries in a long letter from the main character Ramatoulaye Fall to her best friend Aissatou following the sudden death from heart attack of Ramatoulaye's husband Modou Fall. The letter is written while Ramatoulaye is going through 'Iddah, a four month and ten day mourning process that widow of the Muslim Senegalese culture must follow. Ramatoulaye begins by recalling and describing the emotions that flooded her during the first few days after her husband's death and speaks in detail about how he lost his life. She transitions the tone and time by discussing the life she had with her husband, from the beginning of their relationship to his betrayal of a thirty year marriage by secretly marrying his daughter's school best friend to the life he had with his second wife. Throughout this short and compelling novel, Ramatoulaye details to Aissatou, who experienced a similar but different marital situation, how she emotionally dealt with and was changed by his betrayal, his death, and by being a single mother of many.

About the author [wiki]:

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, whose two French-language novels were both translated into more than a dozen languages. Born in Dakar, she was raised a Muslim.

Bâ was born into an educated and well-to-do Senegalese family of Lebu ethnicity. Her father was a career civil servant who became one of the first ministers of state. Bâ was a prominent law student at school. During the colonial revolution period and later, girls faced numerous obstacles when they wanted to have a higher education. Bâ's grandparents did not plan to educate her beyond primary school. However, her father's insistence on giving her an opportunity to continue her studies eventually persuaded them. In a teacher training college, she prepared for later career as a school teacher. She taught from 1947 to 1959, before transferring to the Regional Inspectorate of teaching as an educational inspector. Bâ was married three times and had nine children; her third and longest marriage was to a Senegalese member of Parliament, Obèye Diop, but they divorced.

Bâ neither accepted the label "feminist", which for her was too loaded with Western values, nor agreed with the traditional Senegalese Muslim values for women. According to Rizwana Habib Latha, the character of Ramatoulaye in So Long a Letter does portray a kind of womanism, and Bâ herself saw an important role for African women writers:

The woman writer in Africa has a special task. She has to present the position of women in Africa in all its aspects. There is still so much injustice. . . . In the family, in the institutions, in society, in the street, in political organizations, discrimination reigns supreme. . . . As women, we must work for our own future, we must overthrow the status quo which harms us and we must no longer submit to it. Like men, we must use literature as a non-violent but effective weapon.

Memorable Quotes:

Friendship has splendors that love knows not. It grows stronger when crossed, whereas obstacles kill love. Friendship resists time, which wearies and severs couples. It has heights unknown to love.

The power of books, this marvelous invention of astute human intelligence. Various signs associated with sound: different sounds that form the word. Juxtaposition of words from which springs the idea, Thought, History, Science, Life. Sole instrument of interrelationships and of culture, unparalleled means of giving and receiving. Books knit generations together in the same continuing effort that leads to progress. They enabled you to better yourself. What society refused you, they granted.

Each life has its share of heroism, an obscure heroism, born of abdication, of renunciation and acceptance under the merciless whip of fate.

I am stripping myself of your love, of your name. Clothed in my dignity, the only worthy garment, I go my way.

Even though I understand your stand, even though I respect the choice of liberated women, I have never conceived of happiness outside marriage.

Those women we call ‘house’-wives deserve praise. The domestic work they carry out and which is not paid in hard cash, is essential to a home. Their compensation remains the pile of well ironed, sweet-smelling washing, the shining tiled floor on which the food glides, the gay kitchen fill with the smell of stews. Their silent action is felt in the least useful detail: over there, a flower in bloom placed in a vase, elsewhere a painting with appropriate colours, hung up in the right place.

A working woman is no less responsible for her home. Try explaining to them that nothing is done if you do not step in, that you have to see to everything, do everything all over again: cleaning up, cooking, ironing.

Questions that arose:

How does Ramatoulaye's life in Africa and Aissatou's life in the United States differ? How do their view of men and marriage differ? Why does Ramatoulaye decide to stay married to her husband, while her friend divorces hers.

How would you describe the relationship between Ramatoulaye and Aissatou? How is the bond of sisterhood portrayed?

What did you think of the tone and style of the author? The book is translated from French - how do you think the translation could have impacted the experience of reading?

What did you think about the treatment of women—in terms of upbringing, training, and cultural restrictions—in Senegal?

Last month’s Recap: Our January read was Big Friendship and we had a very lively meeting reflecting on our closest friendships and how they have changed us, and what old and new rituals we could pledge to sustain and care for these deep bonds.

FRIENDLY Reminder, Our theme for the first three months of 2022 is Friendship.

SHELF INDULGENCE PICKS:

January: Big Friendship: How We Keep Each Other Close

February: So Long A Letter

March: Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe

Happy reading and lots of love,

Miti and Tvisha

P.S. If you’re interested in being a part of Shelf Indulgence, write to us!